The complications of imaginary filmmaking: Jamie Shovlin’s ROUGH CUT

How do you remake a film that never existed?

In 1973, Orson Welles gave the world F FOR FAKE; a strange amalgam of a film, one that intertwined fakery with real life but did so with upfront honesty. His blatant proclamations told the audience that the movie would lie to them, trick them, and occasionally reveal the truth. It’s a marvel to experience this masterful deconstruction of film where the unraveling of reality actually feels really…real. Forty years later, UK artist Jamie Shovlin’s continues Welles’ breakdown of narrative and influential imagery in cinematic form with his debut film ROUGH CUT. But while Welles provides a his disclaimer upfront, Shovlin’s magic relies on a back-story that has been a part of an art project for the past few years. What does that mean? Well, ROUGH CUT is a documentary about the re-making a film, HIKER MEAT, that never actually happened. And despite what you will see in ROUGH CUT, HIKER MEAT will never exist. Confused? You won’t be…

The basic premise is this: HIKER MEAT is an imaginary film by a fake Italian director named Jesus Rinzoli that artist Jamie Shovlin, writer Mike Hart (name is an anagram for Hiker Meat), and musician Euan Rodger created in order to give scoring credit to another fake project, the band Lustfaust. ROUGH CUT is the culmination of these projects, a documentary that shows how Shovlin and his crew re-constructed scenes from infamous horror films in order to “make” the new version of HIKER MEAT. As the titles, trailer and imagery suggest, Shovlin culls from horror and exploitation genre history to reconstruct films that are easily recognizable to any horror fan: EVIL DEAD, OPERA, TORSO and A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET III (amongst many others).

Referenced and re-made as closely to the original as possible, using the English countryside as the stand-in landscape for mainly American films, Shovlin creates a metaphoric and literal combination of horror clichés. These individual scenes taken from different films share in specific genre tropes (for instance, there is the prominent fixture of the ‘Final Girl’) but they are, at their core, different stories. By showing the construction of attempting to recreate these scenes and suggesting that they will be cohesively pieced together, ROUGH CUT is more of a revelation of the mystery and magic of cinema rather than a simple montage. So while ROUGH CUT focuses on the attempt to remake parts of HIKER MEAT, HIKER MEAT is only a construct. The narrative lies in the making.

Existing only in trailer form, posters, artwork, and installation piece, HIKER MEAT is fascinating precisely because while it is present in the world, it’s not really there. As Shovlin says, “HIKER MEAT is effectively the false hand that allows ROUGH CUT to exist.” You’ll see glimpses of its potential life in ROUGH CUT, but the desire to see the outcome misses the point. Instead, we should revel in the mystery and take away what’s at the heart of the film: the joy, tribulations, complications, hilarity, and insanity that come with the territory of making a movie. The fact that they’re making something that’ll never exist in a traditional image form is what makes the film uniquely fantastic. That’s the touchstone of reality in ROUGH CUT.

This originally appeared on Fangoria in June 2014.

Nitehawk Naughties: Reclaiming 1970s Porn

As I embark on a new erotic film series in 2015, here’s a look back at what I programmed for the 2014 Nitehawk Naughties series…and why.

I am a woman and I programmed a year-long dirty film series at Nitehawk Cinema.

It seems important to point this out given that some of the recent press covering the series and the current interest in “vintage porn” has had a distinctively male voice. I suppose it’s natural to assume that porn equals “just for men” but there is so much more to screening these older films now than to arouse a man.

I took the helm of our 2014 signature series Nitehawk Naughties program last year originally intending to highlight older sex pics ala Doris Wishman, of whom I’m a huge fan and who is an essential influence for both porn and mainstream cinema. However, my idea truly formalized when a friend posted a link to Vinegar Syndrome’s digital release of The Sexualist and I went down the proverbial rabbit hole discovering their commitment to restoring and historizing a golden era of porn and cult films (see the New York Times feature “Smut, Refreshed for a New Generation”). Learning of their archive made it impossible for me to think of any other direction of the series. This is reason number one: preserving cinema of any genre so that it can reach new audiences is vital to cultural history and should be an integral consideration in film programming.

The Nitehawk Naughties program I’ve put together presents six films spread out through the year (there’s a pretty fabulous “Naughty Summer” section taking place in June, July, and August – get it, it’s hot?) that include: Radley Metzger’s The Opening of Misty Beethoven in 35mm (1976), Evil Come, Evil Go (1972), The Telephone Book (1971), The Sexualist (1973), Memories Within Miss Aggie (1974), and Wakefield Poole’s Bible! (1974). Made during the same period as the iconic Deep Throat (1972), a movie that broke ground in reaching a more mainstream audience, this era represents a crucial time in porn that focused on the act of filmmaking as much as much as the sex. With actors, innovation, and even social commentary, it’s important to remember that these films were made to be played in a movie theater. This is reason number two: in our immediate digital age of amateur and overabundant porn, I want to this era of 1970s porn back where it was originally intended to be seen…the cinema. This is not for nostalgic purposes but rather to reclaim a cinematic space for an often wayward genre.

Speaking of genre film, Nitehawk is no stranger to programming horror movies. The inevitability of the trauma experienced culturally from the Vietnam War, the disillusionment experienced at the end of the hippie movement, the full-fledged second wave of feminism, and all the social unrest that came forth from the late 1960s is all subtextually there in porn and horror from the early 1970s. And that the intensity of horror is seen as somehow, even if marginally to some, more acceptable than its sister corporeal genre of porn seems to be an enormous oversight. Think of how the violent eruptions in Wes Craven’s directorial debut The Last House on the Left (1972) or Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) were intended to invoke Vietnam traumas back in America. Then consider how pornographic films imbue the search for self, the quest for morality and righteousness, and question the sexual liberation of woman all through the explicit representation of taboo acts. This is reason number three: to put 1970s porn into the same socio-political and corporeal context as the horror genre.

The six films included in our Nitehawk Naughties series detail a woman’s life journey. Yes, this journey is through sex that is often in relation to or in opposition of a man, but the women in these sex films have ownership to their actions. Whether it’s looking back at an intensely passionate life or whether it’s in an attempt to save souls, the female characters here own their sexuality and isn’t that what is ultimately desirable? This is reason number four: sexuality in film shouldn’t be solely associated with a man’s pleasure. Showing this past moment in porn just might give us perspective on the male gaze, cinema, audience, female pleasure, and humor.

Originally published on Nitehawk Cinema’s blog, Hatched (January 2014)

Catch Catch a Horror Taxi, I Fell in Love a Video Nasty

British popular culture collides with the influence of horror films in the midst of the Nasty scandal in 1980s UK.

Final Girl Podcast with Bitch Media

In October, I chatted all things women in horror with Bitch Magazine in relation to the Final Girl series I programmed at Nitehawk. Of course, architecture and Carol Clover were discussed…

Better Than No 2: The Bride of Frankenstein

Welcome to a new world of Gods and Monsters…  James Whale had a knack for making horror literary staples like the creeping creaking house, demented scientist and classic monsters appear even darker on the cinema screen. Although the first Frankenstein film was produced by Edison Studios in 1910, it’s Whale’s 1930 interpretation of Mary Shelley’s novel and Boris Karloff’s iconic portrayal that has become synonymous with our idea of Frankenstein’s monster. With its contrasts of shadows and light and humanization of the monster, Whale’s beautiful version endures as the quintessential moment Frankenstein’s creature was born in our popular culture. Five years after the release of Universal’s hit Frankenstein, Whale did the near impossible by making one of the best movie sequels in film history. The Bride of Frankenstein is a complex weaving of Shelley’s subtext of the moral implications scientific discovery produces along with Whale’s personal narrative of sexual preference by introducing one of film’s first homosexual character, Dr. Pretorious. It takes the small portion of Shelley’s original novel of the monster demanding Dr. Frankenstein produce a female friend for him (which the doctor declines to disastrous consequences) and re-imagines it by having a certifiably mad scientist, Pretorious, blackmail Frankenstein into furthering his living dead creations. Whale boldly kicks things off by visualizing Shelley’s prologue in which she recounts the dark and stormy night she shares her monstrous story with husband Percy Shelley and Lord Byron. This melding of literary history as a launching pad for another re-imagining of the written source is risky move (for starters, she confides that the monster survived) but it works simply because it’s damn well crafted. From this scene, Whale’s celluloid tale of a ‘new world of gods and monsters’ opens up and we’re left with more imagery that solidifies the ever-evolving Frankenstein cultural legacy. Karloff again wholeheartedly embraces his role and makes the monster ever more human and in desperate need for companionship while the bride herself, who is only in the film for mere moments, has become iconic with her electric shocked white-striped hair (played by Elsa Lanchester who is also Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley in the film). If sequels have become synonymous with commercial capitalization, cheesy storylines, and subpar acting then consider The Bride of Frankenstein as one of the rare exceptions along with The Godfather: Part 2, The Empire Strikes Back and Dawn of the Dead. As Frankenstein’s monster continues to be emblematic of the ultimate outsider and commentary on the dangers of scientific meddling, Whale’s Frankenstein and The Bride of Frankenstein endures not only as classic films but as poignant films and, best of all, still very disturbing. This essay was originally published on Nitehawk Cinema’s blog (October 2014).

James Whale had a knack for making horror literary staples like the creeping creaking house, demented scientist and classic monsters appear even darker on the cinema screen. Although the first Frankenstein film was produced by Edison Studios in 1910, it’s Whale’s 1930 interpretation of Mary Shelley’s novel and Boris Karloff’s iconic portrayal that has become synonymous with our idea of Frankenstein’s monster. With its contrasts of shadows and light and humanization of the monster, Whale’s beautiful version endures as the quintessential moment Frankenstein’s creature was born in our popular culture. Five years after the release of Universal’s hit Frankenstein, Whale did the near impossible by making one of the best movie sequels in film history. The Bride of Frankenstein is a complex weaving of Shelley’s subtext of the moral implications scientific discovery produces along with Whale’s personal narrative of sexual preference by introducing one of film’s first homosexual character, Dr. Pretorious. It takes the small portion of Shelley’s original novel of the monster demanding Dr. Frankenstein produce a female friend for him (which the doctor declines to disastrous consequences) and re-imagines it by having a certifiably mad scientist, Pretorious, blackmail Frankenstein into furthering his living dead creations. Whale boldly kicks things off by visualizing Shelley’s prologue in which she recounts the dark and stormy night she shares her monstrous story with husband Percy Shelley and Lord Byron. This melding of literary history as a launching pad for another re-imagining of the written source is risky move (for starters, she confides that the monster survived) but it works simply because it’s damn well crafted. From this scene, Whale’s celluloid tale of a ‘new world of gods and monsters’ opens up and we’re left with more imagery that solidifies the ever-evolving Frankenstein cultural legacy. Karloff again wholeheartedly embraces his role and makes the monster ever more human and in desperate need for companionship while the bride herself, who is only in the film for mere moments, has become iconic with her electric shocked white-striped hair (played by Elsa Lanchester who is also Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley in the film). If sequels have become synonymous with commercial capitalization, cheesy storylines, and subpar acting then consider The Bride of Frankenstein as one of the rare exceptions along with The Godfather: Part 2, The Empire Strikes Back and Dawn of the Dead. As Frankenstein’s monster continues to be emblematic of the ultimate outsider and commentary on the dangers of scientific meddling, Whale’s Frankenstein and The Bride of Frankenstein endures not only as classic films but as poignant films and, best of all, still very disturbing. This essay was originally published on Nitehawk Cinema’s blog (October 2014).

Notes on a Final Girl

Below is a text I wrote for Nitehawk on women in horror film in conjunction with the film program, Final Girl…

“No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality.” ― Shirley Jackson, The Haunting of Hill House

Nitehawk’s Final Girl program celebrates fifty years of women in horror film by highlighting the iconic Final Girl. From Georges Franju’s depiction of beauty obsession in Eyes Without a Face (1960) to Adam Wingard’s role-reversing You’re Next (2011), this series focuses on the depiction of the woman’s role within the fictional realm of horror cinema and its association with the reality of daily life. The series eschews the popular bimbo slasher film stereotype by highlighting iconic female characters who experience a revelatory journey from victim to hero. Her on-screen transformation is hardly ever pretty, brutal by sheer necessity, but it realizes an important power shift: the stereotypical male gaze turns into her gaze and then to ours. Embodying Shirley Jackson’s description of Hill House, the Final Girl’s insane break from an “absolute reality” means that it is up to her, our heroine, to restore order when the familiar world becomes an overwhelming space.

When horror films are in top form they provide an incredible cultural analysis. Historically they’ve dealt with socio-political issues, from racism to capitalism, but gender norms have always been a constant. By addressing the patriarchal culture we live in, horror tells us what the possibilities for change are and, in its own visceral way, adjusts the imbalance. This marriage of women and horror actually traces back to 18th century Gothic novels like The Castle of Otranto and the genre has carried on the tradition all the way up to the self-reflexive postmodern heyday of the 1970s-90s. Because horror has the uncanny ability to simultaneously embrace and explode stereotypes when tackling women’s roles, it reveals a victim-to-survivor figure by depicting the “weaker” sex in a position of power with far superior survival skills and intelligence. This is particularly true when they show the struggle and sublimation of women in/out of domesticity via the haunted or evil house; it’s one constant that pops up in horror films and is the commonality amongst all of the films in our Final Girl series.

The concept of the ‘Final Girl’ put forth by scholar Carol Clover in her book Men, Women, and Chain Saws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film applies directly to Shirley Jackson’s above description of the inherently evil atmosphere that permeates her novel The Haunting of Hill House written more than thirty years earlier. The extreme pressure of coping with an unreal horror that becomes the Final Girl’s reality is a commonality shared amongst many, if not most, cinematic horror heroines and it is an essential part of actually being a true Final Girl. This woman, according to Clover, is the person with whom the audience (regardless of gender) identifies with most because we share in her experience and desire for survival in the very strange land she’s found herself in. And ever since she emerged from the Italian giallo and subsequent American slasher movies of the 1970s and 80s, this Final Girl has become a reliable fixture within horror narratives. That is, of course, until post-post modern horror film tackled our comfortable associations with her head on. Regardless, whether she’s the lone survivor amongst her dead companions or the sacrificial lamb to the monster, the historic representation of women in horror is culturally significant. The two appear to be inextricably bound together.

The House is Bad

I haven’t updated this blog in forever but that will soon change. And what better way to start than by sharing with you all the new issue of OneplusOne Journal, Occult, Magick, Evil and the Powers of Horror. Vol II, that includes my essay The House is Bad. I wrote this essay ages ago and it explores houses in the films The Haunting, House of Usher, and Burnt Offerings that aren’t haunted but are, instead, evil by birth. Touching upon subjects I’m very interested in (space, place, and horror), I’m thrilled to have the first concretized bit of writing from me on the subject is finally published.

An excerpt is included below but I encourage you to read read the entire issue (downloadable here) because it includes an interview with Graham Harman on H.P. Lovecraft and the horror of politeness in Michael Haneke’s Funny Games, amongst other stellar reads. Good stuff.

******

Cinema was born with a house that was bad. In the late 19th century, George Méliès not only laid the foundation for moviemaking but he also established the association of horror and the home with his fantastical short, The Devil’s Castle (1896). Over one hundred years later, the idea of the “old dark house” remains unshakable; the recent phenomenal critical and commercial success of James Wan’s The Conjuring (2013) is but one example of audiences desiring classic ghostly interventions within the familial space. But while the ubiquity of the house as a site from which spirits, psychotic murderers, and demonic forces come forth is genre commonplace, there are a select few films that expound upon the house itself as being evil.

So, what is an evil house? The evil house is considered here as Deleuzian/Bergsonian durational space, one that exists in a temporal status where there is a collapse of pasts and presents, interior and exterior, memories and events. The beginnings for a bad house lay in its construction; the time in which all of the above became embedded into its foundation or, as Roderick Usher says, the house contains, “every evil rooted within its stones.” In the bad house, the horror is unseen. It is not a portal for ghosts nor is it the manifestation of awful historical events. It is a vibrant living being born and transformed from wicked environments that systematically lure, destroy, and, occasionally, protect its inhabitants. Read the rest…

I’m pretty excited about this. I’ve been asked to put together a film program in conjunction with Mike Nelson’s exhibition Amnesiac Hide at Toronto’s Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery. It’ll take place on April 2nd and I’ll be there for a chat about film, the apocalypse, and architecture. Description is below…

Keep Moving: Objects and Architecture in the Apocalypse

Inspired by Mike Nelson’s concurrent exhibition at the Power Plant, Keep Moving: Objects and Architecture in the Apocalypse is a film program of works that use objects and architectural environments as tools to give voice and visibility to the unimaginable. Keep Moving is sculptural cinema featuring Richard Lester’s 1969 surrealist post-apocalyptic farce The Bed Sitting Room preceded with artist films by Aïda Ruilova, Aldo Tambellini, and Elizabeth Price. The program provides a reflection of how objects and space define the void-like world that is in relation to the end of all things. Similar to the “semblance of atmospheres” generated in Mike Nelson’s immersive installations, these films are a pivotal way to address the past, access the present and consider a possible future world.

(Full essay coming soon)

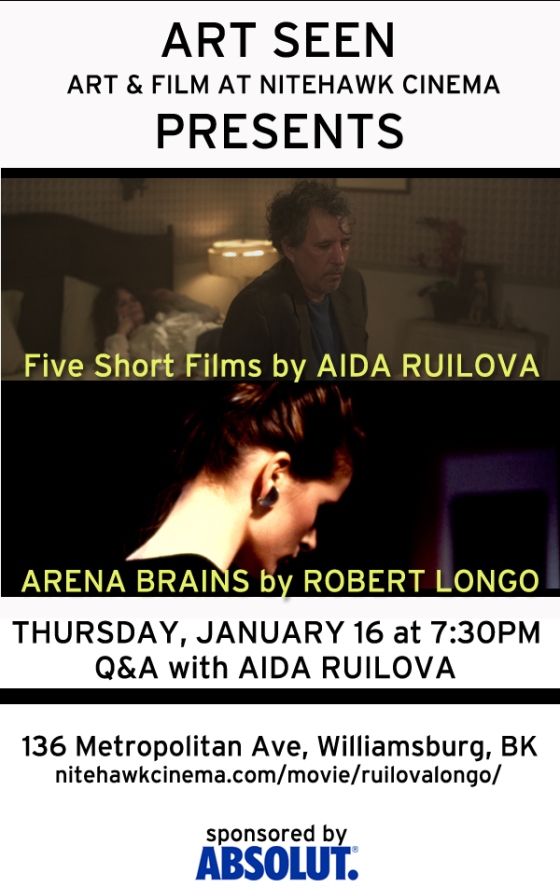

Screening: Aida Ruilova and Robert Longo

My next ART SEEN screening presents five films (including Goner) by Aida Ruilova and Robert Longo’s rarely screened Arena Brains (1987). A consideration of how space and architecture (urban, domestic) can effect us. Get tickets!