Category Archives: Film

Curator gone mad: the 1966 film “It!”

While there are more “artists as villains” in horror films, there are a select few gems of “curators as killers” too (usually involving some sort of occult-practice and historical knowledge). My most recent find it this 1966 British film It! starring Roddy MacDowall as a twisted assistance curator who uses the museum’s newfound acquisition, a 16th century Golem, to increase his standing in life. The museum exteriors and interiors in It! are in London’s impressive Imperial War Museum.

While there are more “artists as villains” in horror films, there are a select few gems of “curators as killers” too (usually involving some sort of occult-practice and historical knowledge). My most recent find it this 1966 British film It! starring Roddy MacDowall as a twisted assistance curator who uses the museum’s newfound acquisition, a 16th century Golem, to increase his standing in life. The museum exteriors and interiors in It! are in London’s impressive Imperial War Museum.

Three Films at Once: Shocking Representation at DAC

Via invitation from Dumbo Arts Center, on Thursday (September 6) I presented a one-night event in support of my upcoming February exhibition at DA On the Desperate Edge of Now (historical trauma in horror film and contemporary art ) with Heather Cantrell, Folkert de Jong, Marnie Weber, and Joachim Koester.

The cabin in the woods: representation and repetition

As I’m writing an essay about the uncanny relationship to Mario Bava’s Planet of the Vampires (1965) and Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979), I’m thinking about the slipages that occur between imitation and homage in creative forms. Where does the impulse come from to manifest a narrative, a style, an atmosphere come from?Where is the boundary border between being on the safe side of homage rather than the evil side of plagiarism? And how does this influence perpetuate the evolvement and dissemination of the horror genre?

In a collusion of similar thoughts, yesterday I looking at the cabin paintings from the 1990s by Peter Doig. Knowing his interest in horror film, seen in his culling from Friday the 13th (1980) imagery, I’ve tended to draw a correlation to this cabin series and the pervasive use of the isolated cabin in the woods in horror films. The claustrophobia of the forrest, shown frenetically and close up in Doig’s paintings, is situated around the idilic solitude of the house. This notion, of course, tends to explode in horror cinema – man is not safe, not even and especially, in nature.

So as I look to Doig’s “homage/influence” from horror, I noticed that perhaps horror film is producing a mutual admiration. How did I come to think this? Seeing the poster for Drew Goddard’s The Cabin in the Woods (2012) I felt something familiar. There was something about that cabin, mirroring itself, reflection both an above world and a reality below that struck a nerve. Then I remembered Doig’s cabin paintings, his layering on imagery, the spatiality he establishes in his work:

Peter Doig – Camp Forestia (1996), Oil on canvas

Peter Doig – Camp Forestia (1996), Oil on canvas

AND THEN…

The similarities between Camp Forestia and The Cabin in the Woods poster suggest that visual art and horror film might just be bouncing ideas (concept and design) off of each other. Intentional or not, this type of intense self-reflexivity means that these ideas about the representation of horror are contagious. My only hope is that there is still room in which to facilitate the production of new generative images and narratives.

Ivan Zulueta – Frank Stein (1972)

Selfishly happy that Ivan Zulueta’s Frank Stein (1972) is back online:

The absorption of the cinematic within Iván Zulueta’s work, Frank Stein and King Kong among them, reacts to the political and social constructs of the 1970s. This is why his version the ‘Frankenstein’ story as subject is so fascinating. Born in the 19th century in a novel by Mary Shelley (Frankenstein 1817), this monstrous tale has been told throughout the decades as a reflection on modern society. In the 1800s, the Frankenstein monster could be read as an allegory on the dangers of scientific explorations or fears of an expanding world. At the dawn of the new decade while the idealism of the 1960s waned, Zulueta’s ‘Frankenstein’ represents the confusion and lapsed innocence of this new world. That Frank Stein is filmed from a television broadcast remarks on the change in media consumption and how its accessibility began to blur the line between information and entertainment. Meaning can seemingly be projected onto this monster in any given era, thereby he perpetually symbolises the recycled, relevant, and rejuvenated spirit of the horror genre.

Future of Film as a Subversive Act

When Amos Vogel (co-founder of the New York Film Festival and Cinema 16) passed away in April at the age of 91, I felt a great loss for culture. Perhaps though, with a re-emergence and re-interest in his legacy, we might now have the chance, with distance, to think about how his actions might inform the way we change and develop the future not just of film but of visual art as well.

When Amos Vogel (co-founder of the New York Film Festival and Cinema 16) passed away in April at the age of 91, I felt a great loss for culture. Perhaps though, with a re-emergence and re-interest in his legacy, we might now have the chance, with distance, to think about how his actions might inform the way we change and develop the future not just of film but of visual art as well.

In small ways this is already happening. This essay by Douglas Fogle on the Frieze blog (a must-read remembrance of Mr. Vogel) is part of this start:

Vogel’s philosophy was that in a democracy it was crucial to offer the public a range of films that would question, enlighten, and enervate with the goal of undermining previous ways of thinking and feeling. Disruption was the path to building new realities and new truths in his mind and his programming rigorously followed this critical methodology throughout his career.

Related: in 2009 LUX initiated a special project at the Zoo Art Fair where they presented artist films that respond to the idea of subversion and the moving image.

You Killed Me First: Cinema of Transgression

The recent You Killed Me First: Transgression of Cinema exhibition (of 1990s New York filmmakers) at the KW Institute of Contemporary Art in Berlin is perhaps one of the most relevant exhibitions that has happened in recent years. While the -innials in New York attempt to foresee the future, You Killed Me First looks back hard at a group of New York artists who quite literally said fuck you in their life, production, and work. It may not all be good or pretty but frankly, we need more of this in art and film. And if we need to look back to do this, then so be it. This exhibition needs to be in New York and Los Angeles anyway.

The recent You Killed Me First: Transgression of Cinema exhibition (of 1990s New York filmmakers) at the KW Institute of Contemporary Art in Berlin is perhaps one of the most relevant exhibitions that has happened in recent years. While the -innials in New York attempt to foresee the future, You Killed Me First looks back hard at a group of New York artists who quite literally said fuck you in their life, production, and work. It may not all be good or pretty but frankly, we need more of this in art and film. And if we need to look back to do this, then so be it. This exhibition needs to be in New York and Los Angeles anyway.

We propose…that any film which doesn’t shock isn’t worth looking at. …We propose to go beyond all the limits set or prescribed by taste, morality or any other traditional value system shackling the minds of Men. …There will be blood, shame, pain and ecstasy, the likes of which no one has yet imagined. – Cinema of Transgression Manifesto

Exhibition ‘zine courtesy of Cliff Lauson who said the show was “relevant to my research”. I quite like that others consider sex, violence, blood, and experimental film in relation to me. Win.

Josh Azzarella: duration, the familiar, and the cinematic

Josh Azzarella is an artist whose moving image works are the result of manipulating known films within popular culture to create an entirely isolated experience. For instance, his breathtakingly immersive Untitled #105 (SFDF) (2009-2011) three-channel installation presses pause on three singular moments within the landscape of King Kong. The work becomes the place where the viewer remains in a perpetual period of waiting for the “monster” to arrive; he never does.

Josh Azzarella is an artist whose moving image works are the result of manipulating known films within popular culture to create an entirely isolated experience. For instance, his breathtakingly immersive Untitled #105 (SFDF) (2009-2011) three-channel installation presses pause on three singular moments within the landscape of King Kong. The work becomes the place where the viewer remains in a perpetual period of waiting for the “monster” to arrive; he never does.

This tension of not-seeing but still knowing expands in Azzarella’s film modification of The Wizard of Oz, Untitled #125 (Hickory) (2009-2011). Admittedly an obsession of his, the familiarity of The Wizard of Oz that is embedded in American culture is profound. From its infamously troublesome production (rumors of suicide, anyone?) to its glorious introduction to technicolor to its popularity through annual television airing, the story of a young girl with dreams who travels to far only to find that what’s important is the love of home is part of America’s narrative. Throughout the world people have seen this film; it’s a universal point of reference.

As with Untitled #105 (SFDF) (2009-2011), Untitled #125 (Hickory) makes the familiar obscure. While we cannot detect any development or movement when watching, we are made aware that it is from a 6 1/2 minute excerpt from The Wizard of Oz; encompassing the moment from when the tornado hits until Dorothy emerges into technicolor Oz and meets Glenda the Good Witch. The reason why we cannot see what we know is there is because Azzarella has stretched out cinematic space and time so that this film, his film, is 7200 minutes, approximately the same time of Dorothy’s stay in Oz. Isolating the film to be entirely represented by a single character’s experience, Dorothy, he says:

As with Untitled #105 (SFDF) (2009-2011), Untitled #125 (Hickory) makes the familiar obscure. While we cannot detect any development or movement when watching, we are made aware that it is from a 6 1/2 minute excerpt from The Wizard of Oz; encompassing the moment from when the tornado hits until Dorothy emerges into technicolor Oz and meets Glenda the Good Witch. The reason why we cannot see what we know is there is because Azzarella has stretched out cinematic space and time so that this film, his film, is 7200 minutes, approximately the same time of Dorothy’s stay in Oz. Isolating the film to be entirely represented by a single character’s experience, Dorothy, he says:

This work extends a moment of transformative transition (Dorothy’s journey to Oz) to envelop the entire time of her experience. Just as dreams which realistically occur in flashes of seconds in our brains can seem like hours or days, so Dorothy’s hours of unconsciousness take on a five day journey of transformation in Oz.

What Azzarella’s interventionist act does is abstract an image so familiar to us that we can no longer recognize it. The naked eye cannot detect movement. The film becomes unwatchable. And why is this important? Because durational films based on popular cinema (also think of Ivan Zulueta’s Frank Stein and King Kong in the early 1970s along with Douglas Gordon’s 24 hour Psycho and Five Year Drive By in the 1990s) force audiences to re-consider ways of seeing. They challenge what we think we know about narrative structure by inverting the movies we know and love as they morph into something new to critique, consider, and debate. These life of this films actually lives on in these works as both a love letter to the story and provocation regarding the fallacy found in cinema. These artists films reveal and remind us that we see onscreen is never really real.

Watch Untitled #125 (Hickory) Part 1 (preview) here: http://vimeo.com/32951541

Fiona Banner: re-imaging cinema

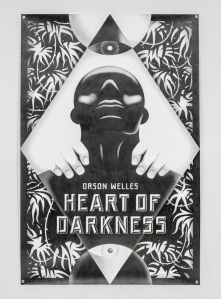

Joseph Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness tackles a real horror, one in both the wilds of the jungle and deep inside of man. Imagine, in the eyes of artist Fiona Banner with select designers, if Orson Welles had made the film adaptation in the 1930s through fictionalized posters. The mind wonders and the eye gawks at these stunning representations of a thing that never fully existed. It plays on notions of the unseeable but knowable, a familiar trope in the horror genre.

Orson Welles wrote a screenplay based on Joseph Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness in the late 1930s. It would have been his first film but it was rejected by the studio RKO, and he went on to make Citizen Kane instead. At the time the script was considered too political, too expensive, and too uncompromising artistically, not to mention narrative parallels with the rise of fascism in Europe. Today other parallels are drawn. – from Artangel’s “A Room for London” program, watch the performance of the script here.

Here are some of my favorite mages from her current exhibition Unboxing: the greatest film never made at 1301PE Gallery in Los Angeles:

The Greatest Film Never Made (Fiona Banner and Name Creative), 2012

Graphite on paper

The Greatest Film Never Made (Fiona Banner and Empire Design), 2012

Graphite on paper

The Greatest Film Never Made (Fiona Banner and La Boca), 2012

The Greatest Film Never Made (Fiona Banner and La Boca), 2012

Graphite on paper

View more images along with installation images here.

Recent writings on horror films

Below is a link compilation of recent writings on horror films that I’ve published on Nitehawk Cinema’s blog, Hatched (where I’m co-editor). Many of these texts correspond to the monthly VHS screenings I co-curate at Nitehawk. Click each title to read the essay in its entirety.

Below is a link compilation of recent writings on horror films that I’ve published on Nitehawk Cinema’s blog, Hatched (where I’m co-editor). Many of these texts correspond to the monthly VHS screenings I co-curate at Nitehawk. Click each title to read the essay in its entirety.

The Collective Monstrosity of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is one of a handful of films that punctuate the very life-blood of cinematic history. Intensely brutal with very little reprieve or consideration for the audience, Texas Chainsaw Massacre came out of a rift of a socio-cultural framework, bursting onscreen with the evisceration of the family structure, youth culture, and cultural fragility in a post-Vietnam United States…

VHS Vault: Tobe Hooper’s Eaten Alive

Everything and everyone in Tobe Hooper’s Eaten Alive looks like it/they need a good, long, hard scrub. The dingy dwellings, saturated coloring, and hazy lighting make an atmosphere that mimics each character’s dirtiness (both inside and out) as well as their visceral insanity. No one here, aside from the little girl and poor pooch, is pure: sex, killing, stealing. Eaten Alive is where vice meets its crocodilian end…

VHS Vault: Flesh for Frankenstein

Dr. Frankenstein and his monstrous creation (often miscalled “Frankenstein”) have seen many iterations of themselves since Mary Shelley first wrote her gothic novelFrankenstein in 1818. Morphing through mediums of literature, theater, film and then television series, commercials, cereals, etc., the “monster” has become the very essence of re-generation – from his “birth” to his cultural evolvement…

VHS Vault: The Exterminating Angel

Luis Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel reveals the slow and sudden unraveling of upper society as they experience an isolated apocalypse in their party hosts’ dining room. Like in other post-apocalyptic movie (zombie, nuclear, vampiric), the unwilling residents of this unknown disaster go through stages of discovery, collaboration, segregation, degradation, and death. Only here, there are no explanations and no reasonable revelations. Buñuel’s beautifully surreal depiction of the decline of bourgeoisie civilization remains unsolved, unknowable, and unexplainable…