Ways of seeing: the fearful role of art in Rod Serling’s NIGHT GALLERY

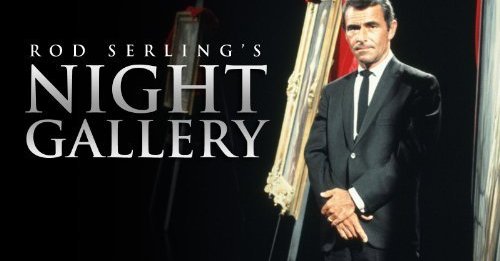

Rod Serling television post-Twilight Zone adventure, Night Gallery, is revolutionary in its usage of art (paintings, sculpture, and art-informed language) as the portal from which its frightful narrative emerges. With each introduction our curator (Serling) shows the audience an artwork that contains, reveals, and is born from the horror story we are about to witness. Here, artwork functions as a way to tell the kinds of stories deemed “unbelievable” or “unreal” – what Night Gallery proposes is that the real is elastic, subjective to our supernatural experiences, and housed within artworks.

Culling often from H.P. Lovecraft (in fact, many episodes are direct visualizations of his stories), Night Gallery shows a speculative reality that places imagined horrors into the realm of the real. Particularly in the beginning of the series, before Serling’s control over production waned, the episodes were present-day narratives in which past actions have otherworldly consequences. In this way Night Gallery is a clear extension of The Twilight Zone, its younger sister functioning as an unfolding morality play to reflect that what we do, the choices we make, matter and affect. It is a fantastical mode of expression for an popular-culture entertainment vehicle such as a television series to ground itself within visual art and to have artwork speak to its viewer. It is a statement that art has the potential for substantive power. Therefore, Night Gallery challenges a notion of how we see, not just artworks or television, but the world around us.

Night Gallery launched as a television movie on November 8, 1969 telling three tales of horror: The Cemetery, Eyes, and The Escape Route. Below I will discuss how each episode embodies the role of artworks and viewership in its depiction of social, political, and personal terrors.

THE CEMETERY. THE PAINTING.

In The Cemetery, a painting on the wall is used as a tool for revenge and murder.

Who could ever imagine that the content of a landscape painting could hold such powers as to make one lose his mind? In the first episode of Night Gallery, Roddy McDowall stars as an estranged nephew who, after killing his elderly and immobilized uncle by parking his wheelchair by the cold open window, gets his comeuppance in the form of a living painting.

Rotten to the core, Jeremy Evans (McDowall) immediately spends his well-earned inheritance on booze, cigars, and partying with the ladies all the while making snide comments to his uncles’ lifelong butler, Portifoy (Ossie Davis). One night, as he drunkenly walks up the staircase, he notices that the nearly unnoticeable painting on the wall has changed…it now shows his uncle’s new grave. Over a short period of time, the painting becomes a vehicle for fear, a virtual television showing Jeremy the unthinkable act of his uncle rising from the grave. No matter what he does – removing the painting from the wall or burning it – will stop its revelations – including showing his dead uncle moving towards the door as the scraping sounds of feet grow nearer to the house’s entrance. The very real terror the painting produces kills Jeremy.

Rotten to the core, Jeremy Evans (McDowall) immediately spends his well-earned inheritance on booze, cigars, and partying with the ladies all the while making snide comments to his uncles’ lifelong butler, Portifoy (Ossie Davis). One night, as he drunkenly walks up the staircase, he notices that the nearly unnoticeable painting on the wall has changed…it now shows his uncle’s new grave. Over a short period of time, the painting becomes a vehicle for fear, a virtual television showing Jeremy the unthinkable act of his uncle rising from the grave. No matter what he does – removing the painting from the wall or burning it – will stop its revelations – including showing his dead uncle moving towards the door as the scraping sounds of feet grow nearer to the house’s entrance. The very real terror the painting produces kills Jeremy.

Out of three episodes, The Cemetery most reflects upon our ability to see (or how we see) paintings and their ability to move us emotionally. Whereas the absence found in post-modern painting connotes a powerful space for meaning to reside, here the absolute presence is what elicits true horror. Things that should remain hidden are revealed while stories that should remain untold, unfold before our very eyes. It’s Jeremy’s insistence and belief in the painting that produces the most affect; one wonders if he didn’t believe what he was seeing, would anything have really happened? Similar to narratives found in other painting-horror films like The Portrait of Dorian Gray, the painting (the art object) becomes a living entity and it is this transformation, from inanimate object to an uncanny animated being that best conveys the real sense of fright.

Out of three episodes, The Cemetery most reflects upon our ability to see (or how we see) paintings and their ability to move us emotionally. Whereas the absence found in post-modern painting connotes a powerful space for meaning to reside, here the absolute presence is what elicits true horror. Things that should remain hidden are revealed while stories that should remain untold, unfold before our very eyes. It’s Jeremy’s insistence and belief in the painting that produces the most affect; one wonders if he didn’t believe what he was seeing, would anything have really happened? Similar to narratives found in other painting-horror films like The Portrait of Dorian Gray, the painting (the art object) becomes a living entity and it is this transformation, from inanimate object to an uncanny animated being that best conveys the real sense of fright.

In a twist move at the end (spoiler alert), Portifoy is seen sipping brandy while talking to the artist he paid to make the successive paintings that scared the young Mr. Evans to death. Now it is Portifoy who will receive the inheritance thanks to his own cunning way of removing obstacles. But what he doesn’t know is that the painting has returned, this time as a real gateway between this world and the next.

EYES. WAYS OF SEEING.

It seems impossible, in fact, to judge the eye using any word other than seductive, since nothing is more attractive in the bodies of animals and men. But extreme seductiveness is probably at the boundary of horror. – Georges Bataille, The Eye

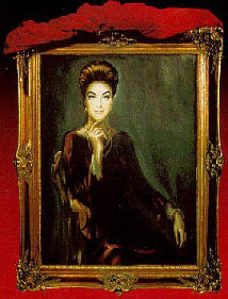

Eyes marks the directorial debut of Steven Spielberg and it is, perhaps not surprisingly, the most visually creative episode of the Night Gallery pilot. Making an overt comment about ways of seeing (or showing things to be seen) through the innovative usage of visuals themselves, Spielberg’s episode is a stunning array of soft focus, contrasting lights, and beautiful montages of crashing class and urban chaos. It stars the estimable Joan Crawford as a very wealthy but mean woman who is blind, she has never seen the treasures she possesses and will do heartless deeds in order to see them for only one night.

Its a triage of immoralities at play in Eyes. One, is the cold rich woman who’ll take advantage of other’s misfortunates for fleeting sight. Two, is the doctor whose young mistress died on the abortion table and is therefore blackmailed to perform the surgery because of it. Three is the rampant gambler whose addiction racked up so much debt that he has to sell his eyes in order to pay it off. No one in Eyes is innocent and yet one, Miss Menlo (Crawford), is clearly the embodiment of evil. And while she gets her eyes in the end, a citywide blackout plays the cruelest joke on her; she believes the surgery didn’t work all throughout the night until she sees the briefest of sun rises.

Its a triage of immoralities at play in Eyes. One, is the cold rich woman who’ll take advantage of other’s misfortunates for fleeting sight. Two, is the doctor whose young mistress died on the abortion table and is therefore blackmailed to perform the surgery because of it. Three is the rampant gambler whose addiction racked up so much debt that he has to sell his eyes in order to pay it off. No one in Eyes is innocent and yet one, Miss Menlo (Crawford), is clearly the embodiment of evil. And while she gets her eyes in the end, a citywide blackout plays the cruelest joke on her; she believes the surgery didn’t work all throughout the night until she sees the briefest of sun rises.

The most moving scene is Night Gallery the one in which Miss Menlo justifies her actions, gesturing to the accessible arrangement of her paintings, sculptures and other acquirements saying, “My eyes will take pictures…pictures to last a lifetime.” It’s true, the purpose for her having this art collection, including multiple portraits of herself, will remain unfulfilled if she cannot see or experience it at least once. And it’s this sense of false purpose that is, quite literally, her downfall. As Bataille suggests, seductiveness is held within the eye but its inherent fragility makes our eyes susceptible to the horrors of the world and its the corporeality in relation to the eye that makes any depiction of them (or sight) in moving images so affective.

The most moving scene is Night Gallery the one in which Miss Menlo justifies her actions, gesturing to the accessible arrangement of her paintings, sculptures and other acquirements saying, “My eyes will take pictures…pictures to last a lifetime.” It’s true, the purpose for her having this art collection, including multiple portraits of herself, will remain unfulfilled if she cannot see or experience it at least once. And it’s this sense of false purpose that is, quite literally, her downfall. As Bataille suggests, seductiveness is held within the eye but its inherent fragility makes our eyes susceptible to the horrors of the world and its the corporeality in relation to the eye that makes any depiction of them (or sight) in moving images so affective.

THE ESCAPE ROUTE. THE MUSEUM.

The final episode in the pilot trilogy is perhaps most unnerving; that’s because it goes beyond the personal experience.

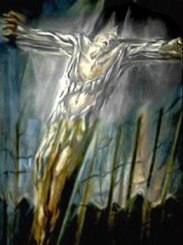

The Escape Route taps into a cultural trauma of post-World War II as told through the Nazi war criminal hiding somewhere in South America. Although the law really is out to capture him, its his own nightmarish memories that he cannot that perpetually haunt him. The only place where he finds solace is in the local museum (an institution with the odd display of dinosaur skeletons and modern painting) where he stares longingly and obsessively at a painting of a man in a boat, peacefully fishing. This painting depicts a quiet space, one of solitude, that promises tranquility and an escape from a painful, albeit self-inflicted, past. So enthralled is the Nazi with the painting, he begins to see himself in it, he witness it move and hears music. He visits the artwork daily, seeing more of himself. He is intently looking, not just at oil on canvas but as a possible other existence.

Throughout The Escape Route, the Nazi repeatedly runs into a concentration camp survivor (twice in the museum, once on the street) who recognizes him from the recent torturous past of Auschwitz. He obsessed with a horrific painting of a man in excruciating agony, crucified on a cross saying that the artist has “captured a nightmare.” He is not escaping his past but dealing with its pain through art. He even challenges the perception of what art can be by suggesting that ugliness in painting is still art and, perhaps, a more truthful representation. The survivor is more progressive in his trauma than the Nazi who, instead of confronting reality, tries to escape it.

Throughout The Escape Route, the Nazi repeatedly runs into a concentration camp survivor (twice in the museum, once on the street) who recognizes him from the recent torturous past of Auschwitz. He obsessed with a horrific painting of a man in excruciating agony, crucified on a cross saying that the artist has “captured a nightmare.” He is not escaping his past but dealing with its pain through art. He even challenges the perception of what art can be by suggesting that ugliness in painting is still art and, perhaps, a more truthful representation. The survivor is more progressive in his trauma than the Nazi who, instead of confronting reality, tries to escape it.

When the police discover where he is, after a German-fueled outburst at a bar, he runs to the only place where he can find solace…the museum. Now, those invested in art are no different in this belief that the museum functions as a place of to escape but here it is quite literally the only place that has the potential to save his life. In utter desperation, he kneels before the painting wishing for God to transport him to the lake, on a rowboat, with the sun and quiet, to get into the picture. And the fantastical does happen, he does successfully merge himself into an artwork, disappearing forever, only he it’s not the lake landscape but, fittingly, the ugly crucification painting. The Nazi is frozen forever in a moment, not one of peace but of contorted pain and agony, a fitting end in a world where a museum doesn’t provide solace and uses its painting as an agent of retribution.

When the police discover where he is, after a German-fueled outburst at a bar, he runs to the only place where he can find solace…the museum. Now, those invested in art are no different in this belief that the museum functions as a place of to escape but here it is quite literally the only place that has the potential to save his life. In utter desperation, he kneels before the painting wishing for God to transport him to the lake, on a rowboat, with the sun and quiet, to get into the picture. And the fantastical does happen, he does successfully merge himself into an artwork, disappearing forever, only he it’s not the lake landscape but, fittingly, the ugly crucification painting. The Nazi is frozen forever in a moment, not one of peace but of contorted pain and agony, a fitting end in a world where a museum doesn’t provide solace and uses its painting as an agent of retribution.

****

In his opening monologue, Rod Serling explains that these stories are suspended in space and time as frozen moments of a nightmare. Using the gallery setting as a background for the display of such self-reflexive narrative and even adopting the function of the curator as the authoritative guide, is such a profound commentary on the relationship between art and horror or, perhaps more specifically, between our existence and horror. This, is the Night Gallery.

gebr.art • press release • for immediate release Original painting from NIGHT GALLERY re-surfaces after 44 years and will be presented for auction in February 2014. Estate custodian Thomas Gebr opens the private collection and archives of the late great Jaroslav Gebr with this truly historic piece of Hollywood Memorabilia.

An original painting by renowned Hollywood portrait artist and muralist Jaroslav Gebr, used in the pilot episode of the cult-classic television series Night Gallery, which was created, produced and hosted by the legendary Rod Serling.

http://www.gebrart.com/exhibits_sales_auctions.html

The answer of an extpre. Good to hear from you.

Well done explosion of the inner workings of the Night Gallery Pilot! I love this kind of unpacking of motive, inspiration etc. of an artists work! I have done a similar thing with Kimbras album VOWS! Look forward to reading more!

Kudos on this article – well thought and executed; fitting tribute to a fave series of mine.